Posthumanism meets Degrowth

What multispecies governance can teach us about systems change

Degrowth offers a powerful critique of an economic system built on extraction and endless growth. But in practice, it often remains human-centred: focused on protecting ecosystems for people, rather than rethinking how humans live with the rest of life.

My thesis started from that tension.

I explored what happens when degrowth is taken seriously as a relational project; one that challenges the assumption that humans sit at the centre of governance and decision-making. To do this, I studied the Zoöp model, an experimental governance framework developed in the Netherlands that formally represents more-than-human interests within organisations through a Speaker for the Living.

To make sure my research was not rooted in abstraction, I conducted ethnographic fieldwork across three sites:

EcoVrede, a grassroots food forest and community initiative (back then) in the process of becoming a Zoöp

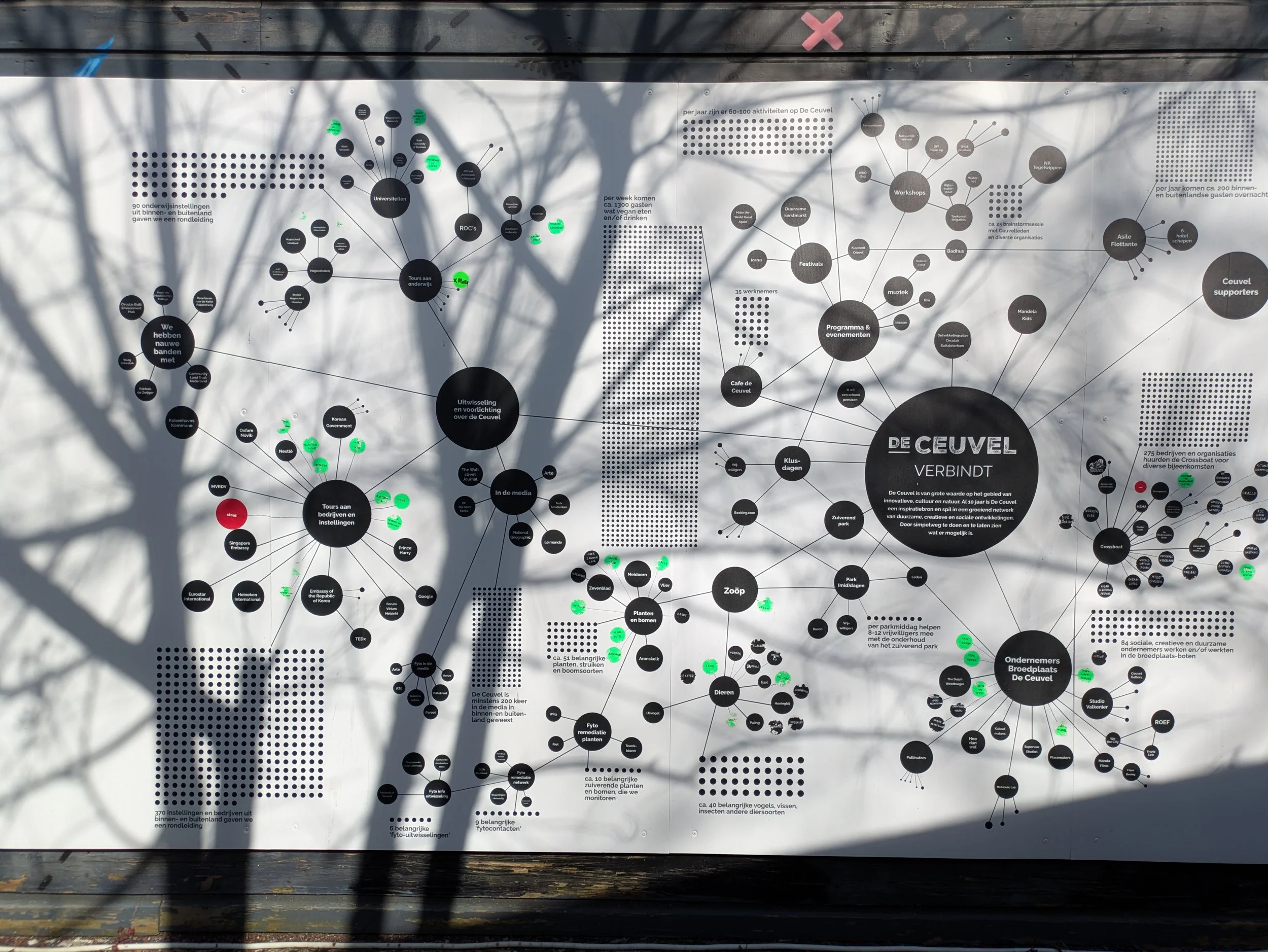

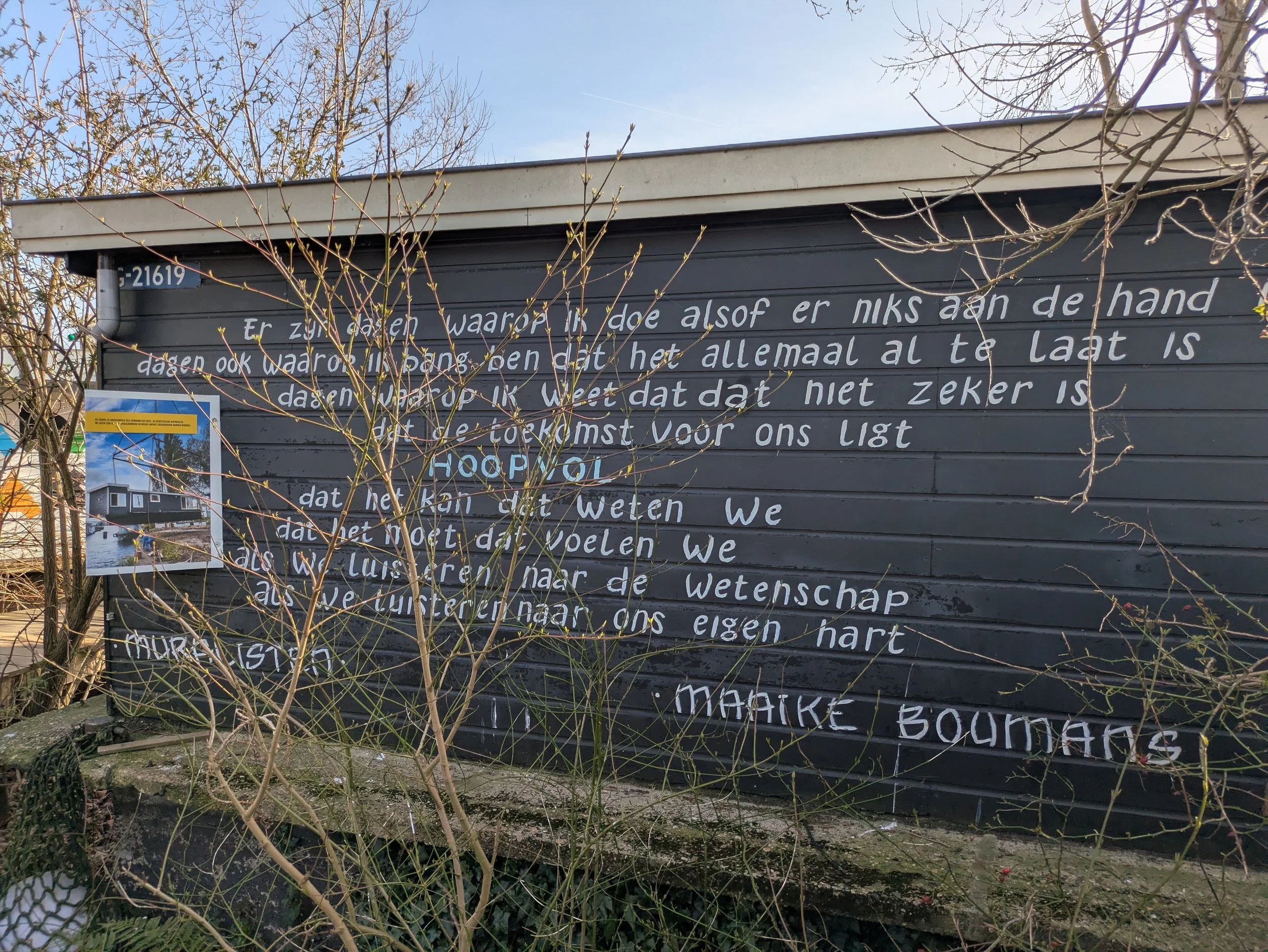

De Ceuvel, an established Zoöp working with regenerative design and circular practices

De Biesterhof, a regenerative farm practising multispecies care without formal Zoöp structures

What emerged was not a neat blueprint for post-growth governance, but something more valuable: a grounded understanding of how difficult, relational, and political systems change actually is.

Across these sites, I observed how people conceptualise “nature” in very different ways. Sometimes as something distant and fragile, sometimes as something to be managed, and sometimes as a co-creator in shared worlds. These conceptualisations mattered because they shaped everyday decisions, conflicts, and forms of care. They also revealed frictions: moments where relational ideals collided with institutional constraints, time pressure, legal frameworks, or deeply ingrained habits.

The Zoöp model, I argue, does not solve these tensions but it amplifies them in productive ways. By institutionalising attention to more-than-human life, it forces organisations to confront the limits of anthropocentric governance and to reflect on what “care”, “responsibility”, and “progress” actually mean in practice.

What this research taught me most clearly is that systems change is not just about better models or policies. It is about changing how problems are framed, whose voices count, and which relationships are considered politically relevant. Degrowth, posthumanism, and governance meet precisely at that point.

What I learned from this project

Analyse complex systems through relational and power-aware lenses

Translate abstract theory (degrowth, posthumanism) into practical organisational questions

Identify frictions between values, narratives and institutional realities and realise these are generative

Work with uncertainty, ambiguity and competing perspectives without collapsing complexity

Skills and strengths demonstrated

Qualitative research & analysis (ethnography, interviews, participant observation)

Systems thinking (linking governance, culture, ecology and economy)

Policy-relevant sense-making (connecting theory to institutional practice)

Reflexive and ethical research practice (feminist, care-based, power-aware)

Narrative analysis (how stories about “nature”, “care” and “progress” shape action)

Translation skills (from complex ideas to accessible insights)